When the Allies Protected the Jews

- Steven Rodan

- Feb 19, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 21, 2024

By Steve Rodan

It was February 1944 and the Allies decided to get rid of the Luftwaffe. Germany's air force had long been a thorn in the Allied campaign during World War II. Four months earlier, the U.S. Eighth Air Force was forced to abort air strikes on Germany and France because of mounting losses exacted by German combat pilots.

Now, it was payback time, and British and U.S. air forces amassed an armada of combat fighters and bombers to destroy the Luftwaffe. The goal was to bait the cautious Germans into air battles while pounding aircraft and related production facilities throughout occupied Europe.

The Allied high command -- Churchill, Stalin and Roosevelt -- knew that Operation Argur would kill many civilians. But collateral damage or civilian deaths played virtually no role in World War II. The death of hundreds of thousands of civilians would mark the price of total war, and the bombing of cities would become policy. The British War Cabinet even coined a phrase for the bloodshed.

Missed by miles

World War II marked the dawn of air power. Hundreds of thousands of sorties were carried out by the Allies and Axis in an effort to avoid ground operations and bomb their enemies into submission. Militarily, the air campaign -- regardless of which side -- was at best marginal. Precision bombing was an oxymoron and targets were missed by miles. Without radar, pilots could not find their targets.

In contrast, even high-flying aircraft could find cities in poor weather. And where the air strikes had the greatest effect was in targeting civilians, particularly in the teeming cities of Europe. In many cases, even the absence of military facilities did not protect civilian communities.

Operation Argur was no exception. In what was known as the Big Week, Allied bombers and fighters attacked civilians on a massive scale. The worst offenders were the Americans. They attacked occupied non-German cities when they couldn't find their targets in the Third Reich.

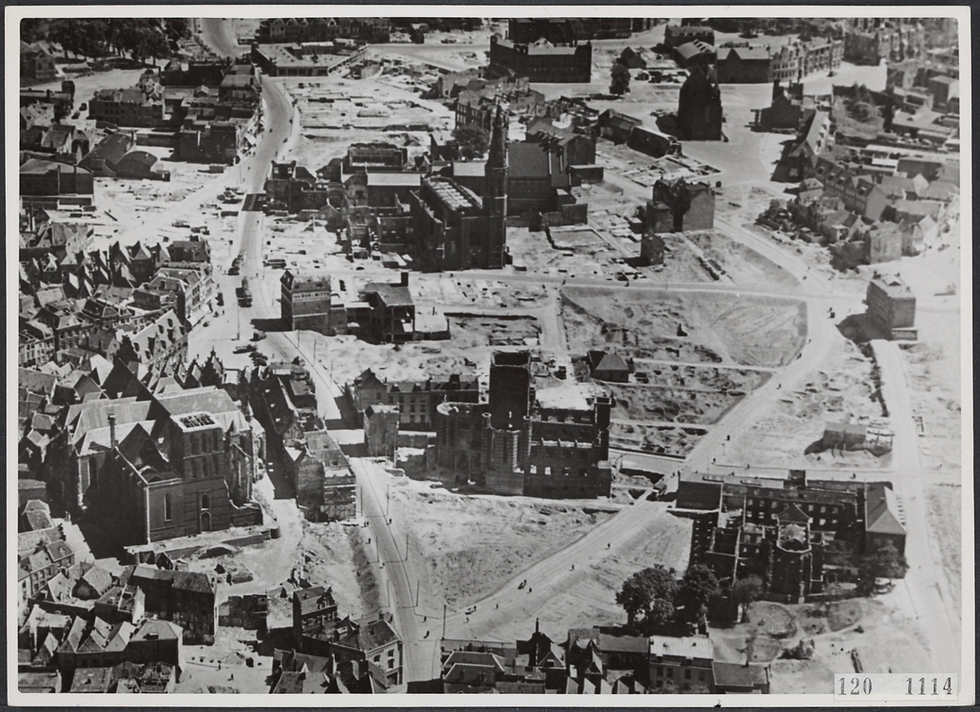

The Netherlands was the biggest victim of Operation Argur. U.S. Air Force B-24 bombers pounded Dutch cities that contained little or no military value whatsoever. They included Arnheim, Deventer, Enschede and Nijmegen. The greatest of civilian casualties took place in Nijmegen when an estimated 880 people were killed. [1]

'Incident'

There were no repercussions -- at least in public-- in killing the innocents. The heavily-controlled media didn't report it. In private, the Allies brushed off the deaths as an "incident." The mantra was that there was a war to fight. As far as the Americans were concerned, they did not regard even friendly civilians as worth protecting.

Britain was more sensitive, only because it harbored exile governments that did complain. Churchill bore the brunt of France's anger in July 1940 when the navy of the newly-occupied country was destroyed by British aircraft. The French government-in-exile was not assuaged by Britain's explanation that it did not want the navy to fall into Hitler's hands.

At times, the assessment of mass casualties in friendly countries made some war planners blanche. In April 1943, the British War Cabinet reviewed a plan to target Germany's transportation facilities, particularly rail depots. The British Defence Ministry submitted an estimate that between 80,000 and 160,000 French and Belgian civilians would be killed in the air campaign.

150 dead civilians per attack

Churchill was concerned with the report. He wanted to keep estimated civilian casualties to no more than 150 for each air operation to avoid an outcry from London's European allies. [2]

The Allies had no such compunction regarding German civilians. Indeed, the bombing of German cities and towns was a leading aim of World War II. As early as 1942, the British War Cabinet approved what was called "dehousing" as a strategic concept. The goal was to destroy the morale of the German people. In February and March of that year, such German cities as Cologne and Lubeck were hit hard, the former losing 59,000 houses in a nightly raid on March 31. In August, 4,000 civilians were killed and 10,000 houses were destroyed in Nuremburg. [3]

Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin were pleased with the results of the bombing of German cities. During a meeting in Casablanca in January 1943, they ordered a campaign that would destroy Germany's military, industry and economic assets. The chiefs also set a secondary goal: "The undermining of the morale of the people."

Six months later, that goal led to the most brutal strike on German civilians. During the last week of July 1943, British and U.S. bombers struck the German port city of Hamburg. Hamburg fit the Allied model of a strategic target. It contained shipyards, U-boat pens and oil refineries. But the Allied attack didn't forget the civilians. In one night, close to 40,000 city residents were burned alive while 60 percent of all houses were destroyed.

Operation Gomorrah

The Allies had worked hard to exact as many civilian casualties as possible in Hamburg. The British and American pilots dropped a payload that combined high-explosives and incendiaries on the northern city. The aim of Operation Gomorrah was to create a firestorm -- a vortex some 460 meters high -- that would spread for miles around. Nature contributed with unusually warm weather mixed with a dry spell. The attack also injured 180,000 Germans. But the Allies hope that survivors would foment an uprising did not materialize.

In early 1944, the Allies targeted the Luftwaffe. Months earlier, the German air force had overcome heavy odds to maul its American counterpart during the latter's efforts to destroy oil refineries, aircraft plants and ball-bearing factories. Allied losses were so heavy that the U.S. Eighth Air Force suspended operations over Germany, allowing the Luftwaffe to maintain air superiority over Western Europe.

Operation Argur, which took place between Feb. 20 and Feb. 25, sought to bait the elusive Luftwaffe into the air and then come in for the kill. The Allies returned to many of the targets that had escaped damage three months earlier. During the operation, Allied air forces flew 6,000 sorties. Losses were heavy on both sides, but the Luftwaffe could not afford them. The German air force lost 262 fighters and 250 airmen killed or wounded, including 100 pilots. It was the beginning of the end. [4]

A debate was sparked in Allied command over other potential targets. Some commanders, backed by Churchill, wanted the priority to be the destruction of Axis oil refineries, particularly the facilities in Romania, a leading oil supplier to the Third Reich. The result was a massive American-led campaign on the Romanian refinery complex at Ploesti, some 60 kilometers north of Bucharest, that began in April 1944. American P-38 and P-51 fighters battled, often unsuccessfully, Luftwaffe aircraft and anti-aircraft artillery.

The attacks on Ploesti came at the expense of what some commanders argued was an even more strategic target: The German railway system that extended into Belgium, France and the Netherlands as well as east into Poland. The U.S. Eighth Air Force was ready to bomb 39 railway targets in Germany. Churchill did not want this, and Roosevelt supported him. That decision would yield terrible consequences throughout 1944. [5]

The Exception

Churchill and his Allied colleagues did make one exception in their policy of targeting civilians during World War II. Throughout 1944, London and Washington rejected pleas for air strikes on Auschwitz and the rail depots and lines that were bringing up to 14,000 Jews a day to the death camp. The Allies first said their warplanes could not reach Auschwitz, a bald lie as an unsuccessful attack on Ploesti in August 1943 involved a flight of nearly 2,000 kilometers from Benghazi, Libya.

Later, Western officials said the Allies could not afford to divert aircraft away from the war effort. Among the excuses was one raised at a meeting of the Jewish Agency of Palestine, the British-controlled bureaucracy mandated to maintain London's rule over the Land of Israel. Opponents of Allied bombing said the attacks would kill Jews in Auschwitz and they couldn't take responsibility for that. [6]

More than 75 years after the end of World War II, the British National Archives released a document from Churchill in which he admitted to concealing information from the Air Ministry so it could not determine the feasibility of bombing Auschwitz. The September 1944 note from Churchill to his private secretary, Jock Colvin, also revealed how the prime minister lied to his government to prevent the destruction of the German camp that killed some 1.3 million Jews.

"So far as I can discover these plans never were in fact communicated to Air Ministry," Churchill wrote. "The Minister of State on Sept. 1 (on behalf of S/S) agreed in writing to the S/S [State Secretary] for Air that in view of the difficulties of the operation of bombing the camps as represented by the Air Ministry (they said they had no detailed inf. of the topography) the idea of bombing them might be dropped." [7]

Notes

1. The Fatal Attack, Feb. 22, 1944, Intent or mistake? Alfons Brinkhuis. Page 147. Weesp. Gooise Uitgeveri. 1984

2. Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945. Richard G. Davis. 2006. Page 246. Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama

3. "War in the Clouds." Royal Air Force, 1942. War in the Clouds (wm.edu

4. Dr. Silvano Wueschner. Feb. 11, 2019. Air University History Office. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama

5. Bombing the European Axis Powers. Pages 233-240.

6. David Ben-Gurion to Jewish Agency Executive, June 11, 1944. Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem

7. Churchill notes to Colvin, Sept. 18 and 20, 1944. British National Archives. Cited in "Admission of Guilt" Steve Rodan. In Jewish Blood blog. An Admission of Guilt (injewishblood.com)

Below: The aftermath of the U.S. bombing of Nijmegen.

Comments